Hand-Framed Wood Roof Structure

2011-10-18

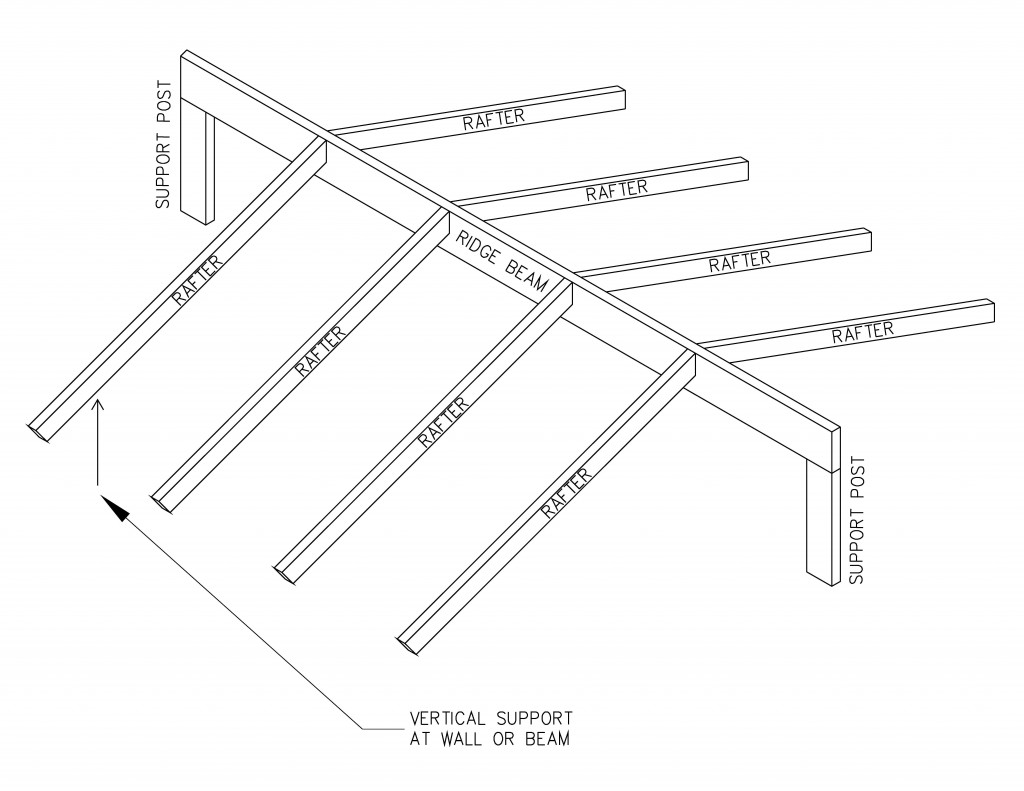

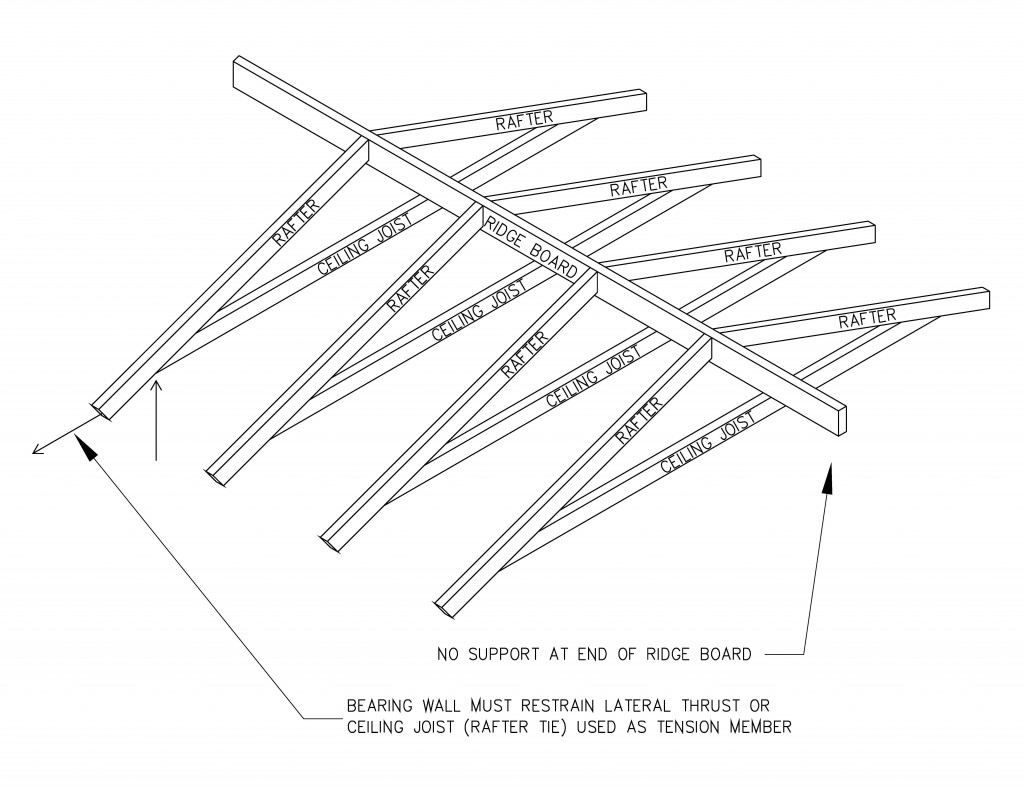

Hand-framed wood roof structures are constructed using different methods and structural principles. The term 'hand framed’ usually means that the roof structural components are assembled on site, i.e. prefabricated roof trusses are not used. There are several different methods commonly used to construct hand framed residential roof structures. Two or more of these methods may be used at different areas of the same home. A hand framed roof structure typically involves several primary structural components. One of these is the roof decking (or sheathing). The decking spans across and is supported by the roof joists or rafters, which is another primary component. These are spaced at regular intervals and may be sawn or engineered lumber, glulam, solid timber, etc. The specific roof structure dictate the presence of absence of some other structural components. Roof decking typically consists of sheathing (plywood or orientated strand board (OSB)) or sawn lumber planks. The decking spans over the roof joists, and therefore must be of sufficient strength and stiffness to transfer their load to the adjacent roof joists without failure or excessive deflection. Wider roof joist/rafter spacing requires stronger decking. Plywood and OSB are typically manufactured in 4’ x 8’ sheets. The thickness varies with the type and application, but 5/8" is common for roof decking. Wood boards, 3/4” thick, are also commonly used for roof decking. Roof joists or rafters support the roof decking. These are regularly spaced members whose size and spacing is determined by their unsupported length (span), their spacing, and the design load of the roof. In the case of flat or low sloped roofs, they are commonly referred to as ‘joists’. A flat roof framed with roof joists is often similar in structure to a hand framed floor structure, except that it is obviously covered with a roofing material and covers or envelopes the top of the home. ‘Rafters’ are effectively sloped roof joists. Two rafters typically meet at a ridge, or top of the roof. A ridge beam or a ridge board should exist immediately beneath and parallel with the ridge. Rafters are often supported by post and beam supports. In this case, the lower end of the rafter is supported by an exterior wall or other support. The upper end of the rafter (at the roof ridge) is supported by a structural beam. Like any other beam, a ridge beam is supported at or near its ends and sometimes at points along its mid-span. The sloped condition of the rafters introduces an additional option with regards to the structural load path, eliminating the need for a ridge beam. Specifically, where flat roof joists require support at or near each end, sloped rafters may be ‘leaned against each other’ at the roof ridge. The top of the rafters are usually placed at either side of a ‘ridge board’, which effectively acts as a block between the two opposing rafters tops under normal gravity loading. In this 'gravity alone' case the ridge board does not provide vertical or lateral support, per se. The rafter-ridge board connection is important with regard to uplift (wind) loading. The ridge board-rafter combination relies on lateral (thrust) restraint at the rafter bottom. This lateral restraint is usually provided by one or a combination of several different mechanisms. One mechanism through which rafter thrust is restrained is through the use of rafter ties. These are horizontal members which often double as ceiling joists. The rafters bottoms are prevented from 'kicking out' (and thus the rafter span and top prevented from sagging) by tension in the rafter tie. This requires that a load path exists between the rafter tie and the adjacent rafter. This load path may be achieved by a direct and proper connection between the rafter tie and rafter bottom. In this case and assuming there are no other connections at the lower supports, the roof would rest on the supporting exterior walls or structure with no uplift resistance other than the weight of the roof itself. The load path may also achieved by properly connecting both the rafter tie and rafter bottom to the support wall or structure. Or both rafter and tie may be connected, with one also connected to the wall or structure. These scenarios result in both thrust (sag) support and uplift restraint. If no tension members are present, the wall or support structure must be capable (either through mass, bending capacity, or other restraint) of withstanding the lateral thrust imposed by rafters that are unsupported at the roof ridge. Historically, buttresses have been used to increase lateral capacity in the exterior walls of cathedrals, castles, arches, etc. The following is a sketch of a common hand framed roof structure using post and beam: The following is a sketch of a common hand framed roof structure using a ridge board and ceiling joists also acting as rafter ties: ADDITIONAL RESOURCES: National Design Specification for Wood Construction Timber Construction Manual Laminated Timber Design Guide